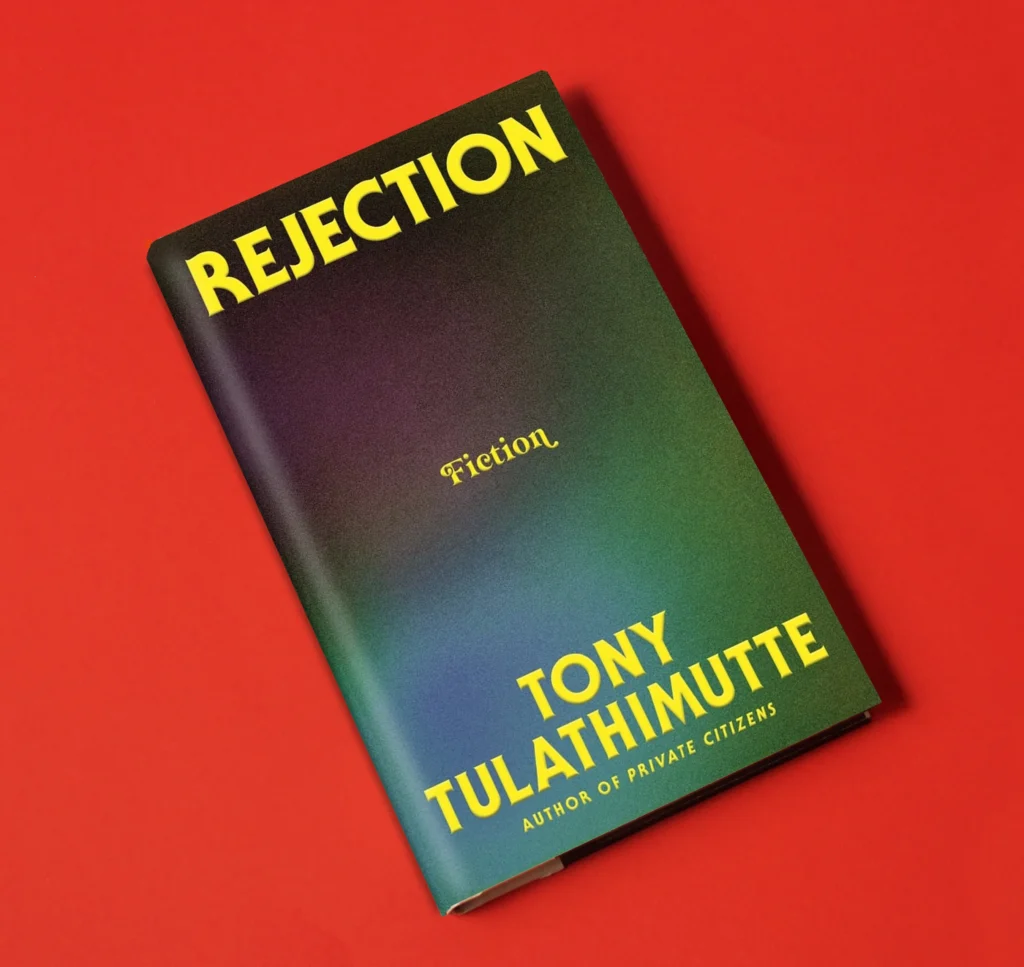

Yesterday, during a flight between Amsterdam and Abu Dhabi, I found myself laugh-crying while reading the final chapters of Tony Tulathimute’s Rejection: Fiction.

Whenever I read a novel, the literature teacher in me always emerges unexpectedly. I think about the didactics of the text and, most importantly, how I could incorporate it into one of my courses. This book would be perfect— but I would never be able to use it.

The text itself is remarkable. The stories are relevant, and the characters are individuals we all suspect exist, akin to cancerous cells on the periphery of society. There’s a white cis-male feminist who eventually becomes an incel because women supposedly can’t overlook his lithe frame and narrow shoulders. There’s a young woman in her twenties who spends years longing for a male friend who had sex with her and subsequently rejected her—leading to digital stalking and encounters with another narrow-shouldered man. By far, the best short story features a Thai-American woman who single-handedly creates a bot farm to pour vitriol into the Twitterverse and even pays actors to lend authenticity to a scandal. The best quote from the book is from this chapter, where Bee states:

“I no longer wanted even me to represent me. To say anything at all from a single monophonic viewpoint, even anonymously, started to feel cringe. So I laid a clutch of alts, mostly on Twitter, some elsewhere. The most successful were the gimmick accounts. My first one was @HoleFoods, where I went to restaurants and, instead of reviewing the service or the ambiance or meal, I posted photos of the next day’s dump, with an account of duration, noise, smell, assfeel, Bristol stool scale rating, etc.”

At this point, Tulathimutte breaks the fourth wall and incorporates himself as a character in the text. While it isn’t quite the same as The French Lieutenant’s Woman, the text could be studied anthropologically in relation to today’s rejects.

Yet, I could never teach this text. In the past, I’ve attempted to use edgy social texts to foster inclusion and offer new perspectives. In 2018, I added Randa Jarrar’s A Map of Home to the first-year bachelor curriculum. I believed a story about a half-Egyptian, half-Palestinian female protagonist who moved around the world would resonate with my students. The majority are children of immigrants with dual identities who constantly feel misunderstood in the West. However, the book includes a passage about female masturbation, rendering it both taboo and passé.

This presents a similar problem with Tulathimutte’s novel. Its acuity is striking, revealing the real grime that exists in online cultures. In “Ahegao, or, The Ballad of Sexual Repression,” the main character has resigned his sex life to a world where he can only pay for specific private sex videos. The young gay Thai-American man Kant’s detailed sexual requests for specialized pornography are so elaborate that they go beyond mere vulgarity— they’re pathological and extremely entertaining to read.

While the format is ideal for my students (short stories in a collection are often easier to handle), and the content would spark debates about sexual and societal norms, it would certainly draw complaints (I’ve been told that my choices of Giovanni’s Room and A Picture of Dorian Gray stem from my own sexuality).

Nevertheless, there’s still a part of me that wants to include this novel. Next year’s students can choose their own literature modules. However, this means I’ll have to do something I despise: provide a trigger warning that reads: “This novel is shocking and includes sexual violence, physical violence, pornography, and more than one reference to feces, and it’s the best book I’ve read this year.”

Geef een reactie